Being an archaeologist often means digging and finding artefacts. But a lot of work is also done from behind one’s desk. I work with heritage protection at the National Trust of Norway, mostly with buildings from the 18th century onwards. The trust applies for funding for different projects, one of those projects was creating a map of historic buildings in an area of Oslo, Norway, with the support of a trust called Sparebankstiftelsen DNB. The aim of the project was to make local heritage accessible to everyone. The project resulted in an online map, a folder, and a guided tour of the area.

There was still money left after the project was finished, and last year we decided to also map archaeological finds and old farms in the area. The oldest buldings that were registered in the previous map were built the 17th century, so we decided to map finds and place-names from the Stone Age up until the medieval period (10,000 BC – AD 1537).

To start the research, I checked the Norwegian heritage databases. Norway has two heritage databases where most finds, sites and buildings in Norway are registrered: Askeladden is for heritage professionals and requires a log in, while Kulturminnesøk is open to everyone. I also visited the archives at the Museum of Cultural History, they have documents concerning archaeological finds. Many of the finds were found in the 19th century, and this information is not always available online. I also read reports from the Agency for Heritage Management in Oslo, they are responsible for archaeological registration projects in Oslo. A lot of books and articles about Oslo’s prehistory were also consulted. Finally, I checked references to old farm-names. Some of the farm names still exist, but we cannot know that they were in the same location.

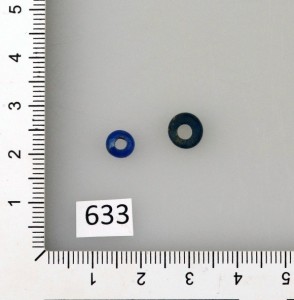

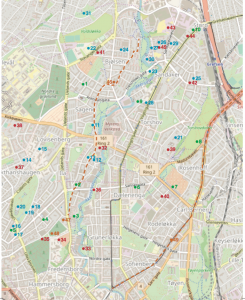

After making a list of the finds, I visited the Museum of Cultural History again. Most of the artefacts are stored there, and it is possible to look at the artefacts and take pictures. In the end, a total of 49 archaeological finds and old farms were chosen to be included in the map. I then had to rewrite the information I had gathered to make them presentable online. Following are some snippets from the exciting finds:

The earliest finds are from around 5000 BC, the later part of the Norwegian Early Stone Age, before agriculture was introduced. These finds are from an archaeological culture called the Nøstvet-culture. One is an axe that was found alone, while a big settlement was found where one of the major roads through town is located today. The remaining Stone Age finds are from the Later Stone Age (4000-1800 BC), mostly axes. There are no Bronze Age artefacts on the map, but some archaeological structures discovered by the Agency for Heritage Management have been dated to the Bronze Age (1800-500 BC).

The majority of the archeological finds can be dated to the Iron Age (500 BC – AD 1050), more specifically the Viking Age (AD 800-1050). It is evident that the area was important and relatively densely populated in this period. Most of the finds are artefacts from graves, such as swords, axes and spear heads. Some burial mounds are still preserved, but they have not been excavated.

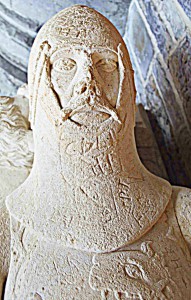

There are also structures that were constructed in the medieval period (AD 1050-1537). One of the structures is a church from the early 12th century that still stands. An old mine still exists beneath the church, the mine was probably exploited already in the 12th century. Two roads still in existence can be dated to the medieval period, but we cannot be sure that they followed the exact same route as today. They are both mentioned in historical records.

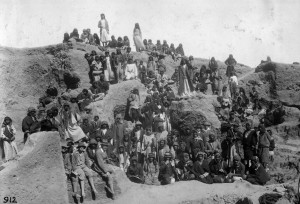

The remaining sites that were researched were 14 old farms. We know that they were in existence in the Iron Age, as we can date the names. Historical records from the medieval period mention the farms, so we know that many of them survived. Some of them exist even today, but it is possible that they were moved several times during their long history. Some of the farms are long gone, and only their names attest to their existence. Interestingly, many of the Iron Age artefacts have been found near were some of the farms are located today.

The aim of the project was to map the history of a part of Oslo. We want people to explore the area on their own, and both maps are available from our office and online.

www.fortidsminneforeningen.no/oa/kulturminnekart/eldre-tids-kulturminner (In Norwegian).

Linn Marie Krogsrud is a Norwegian archaeologist, she works for the National Trust of Norway.