In a blog-post from 27th March 2018 it is stated that people love to destroy things. But they also like to repair them! Today recycling and reuse is very important, but that is not new. Archaelogists all over the world have found items that seem to have been repaired to last longer. Broken pottery has been repaired by drilling holes and then tying shards together with organic materials (rope, leather) or metal staples. Rotten posts in longhouses have been replaced. Brooches have been reinforced with plates from precious metal like silver.

A considerable amount of repaired items have been found in Migration Period graves from the West coast of Norway (c. AD 400-550). This was the material I studied for my Master´s thesis. To find the items I had to search in the common archives of the Norwegian Museums. Most items where tagged with different words to describe a repair or reinforcement. Not all objects were in good condition, and sometimes the description only said that the object had a hole in it. On inspection I could see that the hole could possibly have been caused by a repair.

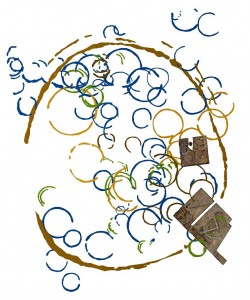

The repaired material from Migration Period Norway consists of glass vessels, pottery, bronze cauldrons and a few brooches. There are different kinds of techniques adapted to the material, but sometimes the techniques used on a material seems to imitate the technique used on a different material.

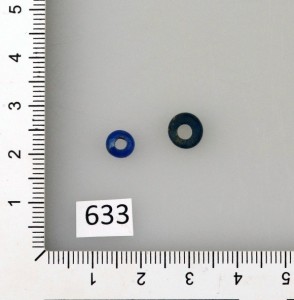

The glass vessels usually had fractures in them, and small holes had been drilled on each side of the crack. Drilling holes without making the the glass crack is a considerable feat. The crack had then been riveted together by pieces made from gold or silver. The glass was also often reinforced by placing a decorated goldband around the rim.

The technique most often used on pottery was to make a new shard from clay. Then they drilled holes in the vessel, and pressed the wet clay from the new shard into the holes. That would create small plugs from the new shard through the holes, and made the new shard stick to the pottery. When it dried it would fit perfectly. Sometimes they recreated the decoration on the new shards.

A different technique on the pottery imitates the one used on glass. Holes would be drilled on each side of a crack, and then riveted together using iron staples.

The bronze cauldrons were mended with bronze patches riveted over rifts or holes. Brooches were reinforced by patching the vulnerable area. One such patch on a brooch has rune inscriptions on it. They are intepreted to mean «this action». Some runes are missing, so the whole content is interpreted to have been «this repair will hold».

The most common thought about why they repaired their things is that they had few resources, so they could not just throw a broken glass or brooch away and go buy a new one. But that is not the only possible explanation. Some of the repairs on the Migration Period glass must have been made by highly skilled craftsmen with access to precious metals, like gold and silver. That does not fit with the explanation that they repaired things because they had few resources. They also repaired pottery made of easily available clay.

In this particular time and place, some of the repairs can be connected to the rise of high-quality ceramic- and goldsmith workers. The decorations on some of the repairs on glass are similar to decorations made on brooches from the same area. The runes on the repaired brooch could have been made by one of these craftsmen who was especially happy with his own work. So maybe they repaired so many things here simply because they could?

A third explanation concerns the age of the repaired things. The glass objects found in the graves were several generations old when they were deposited. It seems that even if they had the resources, they wouldn’t throw away the old glass for a new one. It had to be this particular glass. The glass had a history of its own and was connected to past people and events. That was important to people, and led them to repair things to make them survive longer.

It is funny how small details like repairs on grave materials brings us closer to indiviuals who lived and worked in the past, and how they were thinking about and treating their own past.

Kristin Bakken is a Norwegian archaeologist with an MA in Iron Age archaeology from the University of Oslo. She mostly works as a field archaeologist and is also a volunteer for the National Trust of Norway.