I was at a party last night—one with a very long line for the bathroom. While I was waiting, the girl in front of me struck up a conversation about my work as a graduate student in archaeology.

“Oh wow! So do you go to lots of places?” she asked.

“Yes! I’ve dug in Jordan, Turkey, Kenya, and Virginia.” I replied.

“Really? You actually dig and stuff?” she responded incredulously.

“Yep! I’ve actually dug in all those places. Although, my work is more focused on the people who are affected by archaeological projects. I do a lot of interviewing people in the communities around archaeological sites, asking them what they care about, how much they want to be involved in the excavation, how we can work to be respectful of their needs and desires. So my work is more about the people than the artifacts.”

“Wow,” she answered, and paused. “But, so… do you actually find stuff when you dig?”

This conversation was almost a direct playback of hundreds of conversations I’ve had. If you’re here, surely you agree that archaeology is really cool. Tons of people are eager to learn more about it. I can’t count the number of times a bank teller or fellow dog-owner or high-school acquaintance has told me that their childhood dream was to be an archaeologist.

Although their admission can sometimes be based on a romanticization of archaeology, I actually don’t find this to be the case most of the time. Indeed, many people have read articles in news sources like the Chicago Tribune and the National Science Foundation, or work by archaeologists including Cornelius Holtorf and Anne Pyburn, who have written about the differences between popular presentations of archaeology and the realities of excavation. These discussions are really important to have; as they point out, the swashbuckling, finders-keepers image of archaeology that we are used to from movies like Indiana Jones and Lara Croft leads to real misunderstandings of just how scientific and meticulous archaeological excavation is, and justifies the removal of artifacts from their original contexts or from the possession of the people to whom they rightfully belong.

But even these conversations do little to help non-archaeologists understand just how diverse the discipline of archaeology is. Yes, we measure the specific find-spots of artifacts instead of snatching them and running off. And yes, we record absolutely everything we can from soil color and texture to what tools we used to remove the earth. And yes, we collect, document, and conserve the artifacts that we find.

And then there are some of us, like me, who ask questions that are very indirectly related to the artifacts. For example, more and more archaeologists identify themselves as practitioners of public archaeology, a really broadly-encompassing term that refers to archaeology seeking to involve non-specialists in archaeological research. It can take the form of educating members of the public about archaeological work, or involving descendant community members in planning and executing and excavation, or training local people in analysis and conservation strategies. This blog, in fact, is an example of public archaeology!

Ironically, most non-archaeologists do not know that this sub-discipline is emerging within the larger field of archaeology. When I explain my work, the most frequent question I am asked is, “Is that really archaeology?” And I can’t very well be offended—public archaeology sits in this uncomfortable place where it is still new enough that non-practitioners don’t know about it, even though its entire goal is engaging non-practitioners!

So, in the interest of broadening ideas of what constitutes ‘archaeology,’ I will tell a little bit about my research which, yes, is really archaeology, but might look a little different from what one would expect.

For the past four years, I have been working with the local communities at Petra in Jordan and at Çatalhöyük in Turkey, asking them about their perspectives on the archaeological work that has been completed at these sites. My interest is especially in talking to the men and women who have been employed to work on these projects, to understand what only they know about the sites from both living and working there.

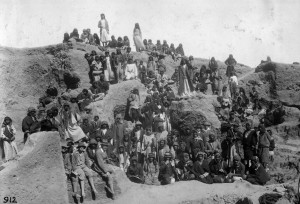

You see, since archaeology began—particularly in the Middle East—excavations have relied on massive gangs of locally-hired laborers to move the soil and expose the remains (see below). In some cases, like the Quftis in Egypt, these workers were trained in specialized excavation techniques and in turn trained their sons, so on through the generations. One group of workmen in Iraq were hired consistently on projects for nearly 100 years!

Petra and Çatalhöyük were both excavated starting in the mid-20th century. These are sites where groups of locally-hired workers acquired unique expertise from working on project after project, season after season, as well as growing up amid these archaeological remains. They learned from their family, they learn from archaeologists, and most importantly they learned from firsthand experience. They became experts in archaeology, without any formal training.

These locally-hired diggers, however, never participated in the documentation, analysis, and publication of the archaeology. This means that their privileged and expert observations and perceptions of the remains have gone formally unrecorded, only handed down through oral history. This is what I aim to recover in my work. By interviewing the people whose families have worked for decades on archaeological projects at these two sites, I’m uncovering some stories and information that has never been recorded before, which can help us to learn even more about the archaeology of both of these exciting places.

So yes, I do dig for artifacts, but what I really love digging for is stories from some archaeologists who have never been recognized as the experts they are. And yes, I travel to lots of places, but when I get there I go into peoples’ homes, if they are kind enough to invite me in, and I record their memories. And yes (as I hope you agree!) what I do really is archaeology.

Allison Mickel is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Stanford University.